Nymphea

The elusive nymphea has awed and inspired across cultures for centuries, symbolizing beauty, peace, femininity, and healing. The root "nymph" represents a feminine soul that had lived in nature. Artists have resurrected this feminine and exotic spirit for centuries, from the Mayans to the late photographer Ren Hang and, perhaps most famously, Monet.

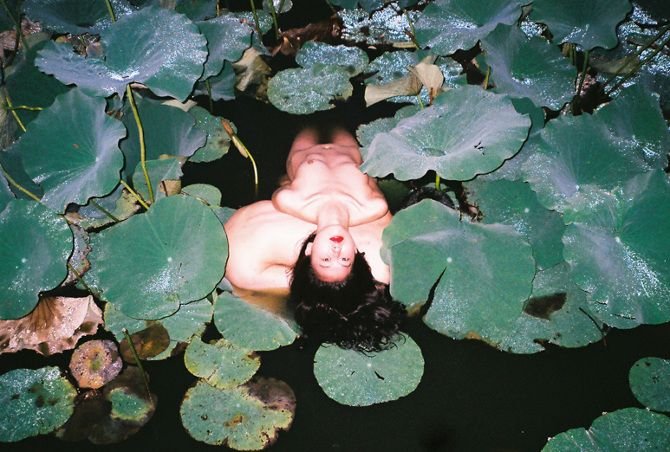

REN HANGS WATER LILIES SERIES

Hang's art is deeply intertwined with Nympheas, embodying nature's sensual and feminine spirit. His imagery features pale, dark-haired women playfully interacting with giant pink Chinese lotus leaves, some floating beneath the murky water, their bodies glowing, while others peek their eyes above the surface.

This scene evokes a sense of freedom reminiscent of ancient Greek culture, where only women that were mythical beings, such as the nymphs lending the flowers their name, or Hetaera with mythical reputations enjoyed such liberties. It prompts thoughts of retelling myths such as Echo and Narcissus or more culturally relevant Cao Zhi's "Nymph of the Luo River." Hang's consistent use of red lips in his nymphs adds a daring layer, emphasizing the boldness of these women and Hang himself, especially considering the series' creation challenged the censorship and conservatism in his native China.

While, Hang once stated, "My pictures' politics have nothing to do with China. It's Chinese politics that wants to interfere with my art” it is hard to ignore the juxtaposition of the delicate, ethereal beauty of the nymphs with the political and cultural undertones in Hang's work. Elevating the significance and impact of his art, portraying the power of both the artist and his subjects.

MONETS LILLIES

Between 1897 and 1926, Claude Monet painted approximately 250 waterscapes of his favorite subject towards the end of his life: Water lilies. The artist once said of the water flowers: "One instant, one aspect of nature contains it all." The cool and earthy surface of the lake dances with light and the life of the white and pink blooms of the lilies and occasional foliage of the surrounding garden, transforming in shades and atmosphere by season or the status of Monet's sight. These famed works almost didn't exist due to the resistance of the French government over concern of the oriental plants poisoning their pristine European landscapes.

While ecological disturbances are a valid concern, it was quite ironic the French so deeply feared the invasion of their native lands and the introduction of foreign influences at a time when they had just closed the chapter on a brutal campaign in "Indochina" and Orientalism was at its peak in Europe with the abundance of looted goods being exported to adorn the stylish homes and people of its elite.

TRANSENDING BOUNDRIES

The nymphea, in its ethereal beauty, transcends the very boundaries humans have tried to impose upon it. From Hang's defiant portrayal of feminine freedom to Monet's obsessive documentation of light and life on water, these artists recognized what political powers often failed to see that beauty cannot be contained by artificial borders or cultural prejudices.

The water lily stands as a powerful metaphor for resilience and adaptation. Just as these flowers float serenely atop murky waters, reaching toward light while remaining rooted in darkness, so too does art persist despite censorship, colonialism, and cultural appropriation. The irony of European resistance to an "invasive" plant while simultaneously extracting resources and artifacts from distant lands reveals the complex relationship between appreciation and exploitation that continues to shape our global cultural landscape.

In both Hang's provocative photographs and Monet's impressionist masterpieces, we find a common thread, an invitation to look beyond the surface, to immerse ourselves in the deeper meanings of beauty, identity, and belonging. The nymphea's journey across cultures and through centuries of artistic expression reminds us that true beauty often emerges from unexpected crossings and fearless transformations, challenging us to question our own boundaries and preconceptions about what is native and what is foreign, what is pure and what is contaminated, what is political and what is simply human.